Published by Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics

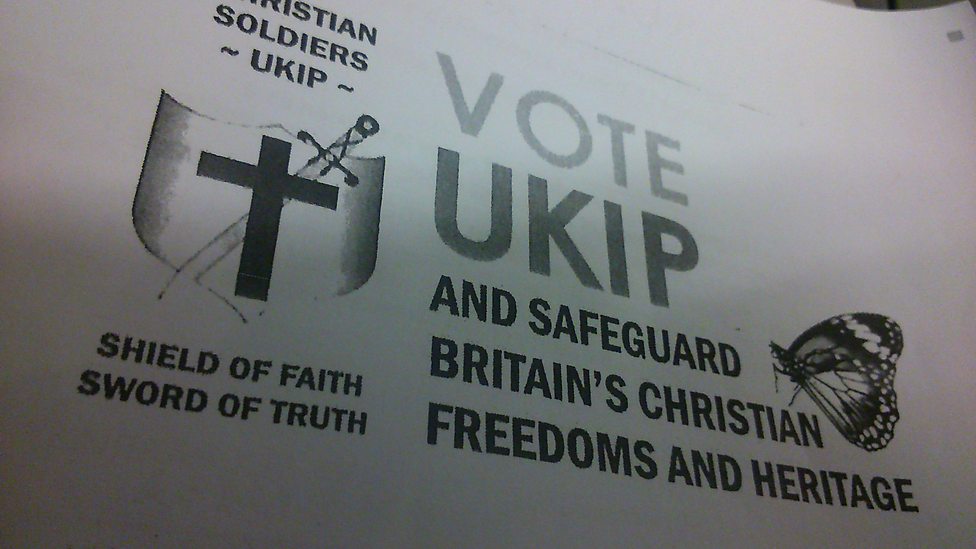

The United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) has made some significant electoral advances since the 2010 General Election, when they secured 3.1% of the popular vote. Not only did the party go on to win the 2014 Elections to the European Parliament with 24 MEPs elected on 26.6% of the vote, but they currently have 430 councillors across 76 local councils, and recently secured their first elected MPs to Westminster following Conservative defections and victory in two volitional by-elections. At the time of writing they are regularly scoring between 12-15% in opinion polls. Christians are deeply divided about the party’s perceived ‘undercurrents’ of racism, nationalism and isolationism which, some aver, put them beyond the pale of religious respectability. But despite episcopal denunciations(1), the party is attracting Christians from across the denominations, including the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church(2).

The United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) has made some significant electoral advances since the 2010 General Election, when they secured 3.1% of the popular vote. Not only did the party go on to win the 2014 Elections to the European Parliament with 24 MEPs elected on 26.6% of the vote, but they currently have 430 councillors across 76 local councils, and recently secured their first elected MPs to Westminster following Conservative defections and victory in two volitional by-elections. At the time of writing they are regularly scoring between 12-15% in opinion polls. Christians are deeply divided about the party’s perceived ‘undercurrents’ of racism, nationalism and isolationism which, some aver, put them beyond the pale of religious respectability. But despite episcopal denunciations(1), the party is attracting Christians from across the denominations, including the Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church(2).

Ukip’s principal raison d’être is the secession of the United Kingdom from the European Union – an objective which invites allegations of ignorance of the organic complexity of the social order, if not imputations of ethical irrationality and political intelligibility. I am not myself a Kipper, but I share their essential disposition toward decisional freedom and the more Whiggish expression of conservatism, based around the themes of democracy, accountability and nationhood. These derive from a particular apprehension of the temporal order: ‘..the most High divided to the nations their inheritance’ (Deut. 32:8). The God who made nations, tribes, people and tongues (Gen. 35:11; Isa. 14:26; Acts 17:26) did so in order to distinguish between ethnic lineage, political culture, religious beliefs and territorial boundaries. The nations are not only disparate and divided, but of variable potency and purpose (Gen. 25:23): they are not all ‘equal’, and cannot be made so by universalist prescriptive decree. As Archbishop Justin Welby recently observed: ‘Equality as an aim in itself through government action is doomed not merely to defeat but to totalitarianism'(3).

It is principally the EU’s anti-democratic polity which concerns Christians right across Europe, not just in the UK. Referendum results which do not accord with the Union’s ‘ever closer union’ trajectory are discounted(4); and democratically-elected governments which do not abide by the fiscal rules of ‘economic governance’ are summarily replaced by EU technocrats(5). The story of the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1-9) is often adduced to support the divine institution of the nation state, by which understanding any man-made attempt to bring an end to the curse of linguistic and cultural pluralism is considered contrary to the purposes of God. For some, the pride and arrogance of Babel are mirrored in the aloofness and anti-democratic unaccountability of Brussels and Strasbourg: ‘the modern age has tended to construe all authority as political authority [and so] the notion of divine authority has become increasingly puzzling to it'(6). If pluriformity in the world order ‘is a capacity for different things to transpire and succeed one another within a total framework of intelligibility which allows for their generic relationships to be understood'(7), then Ukip advocates a notion of governmental authority which is attuned to a biblical hermeneutic as well as the traditional Anglican rubric of tradition, reason and experience.

But the modern British State is distinct from the ancient biblical conception of nationhood – not so much by ideologies of identity, ethnicity, religion or culture, but by its model of governance, protected borders, military security and an organic social concord propagated by a national system of education, a common language, currency, taxation, justice and the rule of law. It is dangerous to draw too precise parallels between historic conceptions of nationhood and those of the present, or even of past empires and the modern European one, as Boris Johnson did with Rome and the EU(8). Nevertheless, certain parallels may be observed, as Alasdair MacIntyre notes:

A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve – often not recognizing fully what they were doing – was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness…. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us(9).

And MacIntyre is uncompromising in his observation of both the cause of and solution to the pervasive social pessimism:

This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for Godot, but for another – doubtless very different – St Benedict(10).

The localised attributes of national sovereignty and community civility are fundamentally challenged by the overriding and coercive moral-political ‘Euro-nationalism’ emerging from Brussels and Strasbourg. MacIntyre doesn’t specify the secular darkness of the European Union, but by invoking St Benedict, the reputed founder of Western monasticism, he alludes to lay communities comprised of individuals who are zealous for God; who are determined in their flawed brotherhood to reflect, worship and submit to a life of virtue for the good of human community. As St Benedict found, this is best achieved not by the grandiose visions of a prescriptive religious order, but by the conversion and renewal of individual hearts, who then dwell voluntarily in autonomous communities of mutual service and submission under the authority of a local abbot.

While the founding fathers of the European Coal and Steel Community/European Economic Community were devout Christians intent on forging a European union in order to neutralise the means of production and negate those nationalisms which historically had led to war, it has become increasingly apparent that the project of ‘ever closer union’ is deeper than mere matters of politics and economics. The objective is to create a distinct European cultural identity, if not a ‘A Soul for Europe’ – a project with a declared Mission Statement which is somewhat antithetical to The Rule of St Benedict: ‘We connect communities in order to build a common European public space and a culture of proactive citizenship'(11). The group is supported by the Commission of the Bishops’ Conferences of the European Community (COMECE), the objective of which is ‘To monitor the political process of the European Union in all areas of interest for the Church'(12). The values of ‘A Soul for Europe’ are European to the extent that they are influenced by the heritage of Christendom and the politics of the Enlightenment, but religious liberty is now imperilled by the imposition of a secularised concept of human rights. Recall the fate of Rocco Buttiglione – Italy’s nominated European Commissioner in 2004 – who was rejected when his orthodox Christian views on matters of gender and sexual morality became known to his parliamentary inquisitors. There are justifiable fears that there is diminishing ‘public space’ in this socially-liberal project for adherents of social conservatism.

By challenging the supranational catholicity of ‘ever closer union’, Nigel Farage hammers his 95 theses to the doors of the Europe’s cathedrals of secularity. Ukip becomes an army of protestants, defending British national culture and traditions from the latest threat to emerge from Rome. England was declared a sovereign state under God during the Reformation, when, in 1533, Thomas Cromwell brought before Parliament the Act in Restraint of Appeals. It decreed:

This realm of England is an Empire … governed by one Supreme Head and King having dignity and royal estate of the imperial Crown of the same, unto whom a body politic, compact of all sorts of degrees of people divided in terms and by names of spirituality and temporality, be bounden and owe to bear, next to God, a natural and humble obedience.

God’s design is for diversity and plurality, and for the executive levers of power to be held in tension in order to mitigate sin and corruption. Ukip’s ethic of governance is to resist political centralisation and social uniformity. Thus the sovereignty which hinges on currency – ‘render unto Caesar’ – is inviolable. As the Talmud says: ‘He is the king of the country whose coin is current in the country’, and so the euro must be resisted because it diminishes economic independence, restricts governance and subverts democracy, as the Greeks are currently (re-)discovering. The story of Naboth’s vineyard (1 Kings 21) suggests that those in authority are not free to pursue any policy they please or to ride roughshod over the rights of the poor. God demands justice and peace above economic conviction. When these are ignored, we witness increases in civil unrest and nationalist idolatry, as we are currently across the EU, principally because un-owned traditions are imposing themselves on public life and the substance of community is no longer held in common.

Christians for whom the political imperatives are to protect human life, respect human dignity, encourage the family and maintain individual liberties find it increasingly difficult to do so in an intolerant political union where morality is relative but always subject to the ethical primacy of secularity. Certainly, Christians in Europe are free to worship in their church buildings, but increasingly less may they walk in spirit and in truth in the public space. Whilst accepting that all political parties seek to strengthen the institution of the family as the stable foundation of stable society, it is to be observed that Ukip alone has upheld the uniqueness of the Christian (indeed, Jewish, Islamic and Indic) moral orthodoxy of the heterosexual marriage union. It is undeniable that very many Christians have been attracted to Ukip solely on the basis that they opposed same-sex marriage.

It would be a mistake, however, to interpret this as evidence of Ukip’s higher moral concerns: as a political party in a liberal democracy they adopt pragmatic policies to maximise appeal and then make their overtures of sophistry to secure a vote. Equally, however, it would be a mistake to believe that Ukip is value-free: their understanding of national stability and social unity is predicated on the inculcation of what they term ‘Judaeo-Christian’ values, and there are sufficiently devout Christians (and Jews) in the party to ensure that moral considerations are foundational to policy development. Ukip’s Christian MPs, MEPs, councillors and supporters are committed to a model of social justice predicated on the diffusion of political power – subsidiarity – and economic collaboration of the sort that exists within the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). Their patriotism inclines to what Burke called ‘the grand chorus of national harmony’. While many Christians favour deeper EU integration for noble and virtuous reasons, the Ukip-inclined Christian believes that the centralisation of power and anti-democratic forces which sustain it are ultimately contrary to the foundational principles of righteous government. Christians have become used to openness, accountability, participation and the application of the free conscience. While global problems such as poverty, famine, disease, international fraud, drug-trafficking or environmental concerns do not stop at national boundaries, Ukip’s preference is for intergovernmental cooperation which sustains democratic legitimacy, rather than notions of ‘pooled’ sovereignty. It may be observed that the Church has been at the prophetic forefront of meeting some of the most pressing global needs without the need for sovereign competences.

Ukip’s sense of solidarity, like charity, begins at home. It is discovered ‘by entering into those relationships which constitute communities whose central bond is a shared vision of and understanding of goods'(13). There are ways of balancing national loyalty with wider fraternity without assertions of nationalist supremacy. Articulated by flawed moral agents of partial political understanding, they may not always get the balance right, but their vision is essentially one of a Europe in voluntary communion with its constituent members, rather than one which imposes its own infallible sense of legitimacy and serves the will to power. Ukip, without recognising it, is almost Benedictine in its conception of the good insofar as their participatory quest begins with the individual and is thence nurtured by and in community. And that community is authentic because it is spontaneous, organic and consensual. It may not represent visible unity, but it is certainly a reflection of peaceful collaboration, reciprocal interdependence, and a witness to an alternative Europe.

_____________________________

(1) See, e.g., Pete Broadbent, Twitter, 26 May 2014, [1], [2]; Christopher Lamb, ‘Bishop cautions against Ukip as Catholics urged to join in EU vote’, The Tablet, 12 May 2014.; Rowan Williams, ‘Why don’t Christians care about politics?’, Opening address, Faith in Politics conference, City Temple, London, 28 Feb 2014.

(2) A recent poll put Ukip support at 18.3% of Anglicans and 12.9% of Roman Catholics. For other denominations, see British Election Study 2015: Religious affiliation and attitudes.

(3) Trinity Wall Street symposium ‘Creating the Common Good’ (22 January 2015).

(4) As seen in Denmark (Maastricht Treaty, 1992), France and Netherlands (Constitution for Europe, 2005), and Ireland (Treaty of Nice, 2001; Treaty of Lisbon, 2008).

(5) As seen in 2005 in Greece, with the appointment of Lucas Papademos; and in Italy, with the appointment of Mario Monti. Both were EU technocrats, and neither was democratically elected.

(6) Oliver O’Donovan, Resurrection and Moral Order (Apollos/IVP, 1994), 122.

(7) Ibid. 189.

(8) Boris Johnson, The Dream of Rome (HarperCollins, 2006).

(9) Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue 3rd ed. (University of Notre Dame Press, 2007), 263.

(10) Ibid.

(11)‘A Soul for Europe’, Mission Statement.

(12) European Commission, BEPA Archives.

(13) MacIntyre, After Virtue, 258.